by Becca Shaw Glaser August 10, 2021, The Free Press

“We need to treat this as the emergency that it is. We should create a public campaign asking people to open up their homes now. If this were a refugee crisis there would hopefully be people and groups organizing to open up homes to house people; we need to respond to this housing crisis with similar urgency and care for our community members who are suffering right now.”

— Amy Files, artist, designer and community crganizer, Rockland

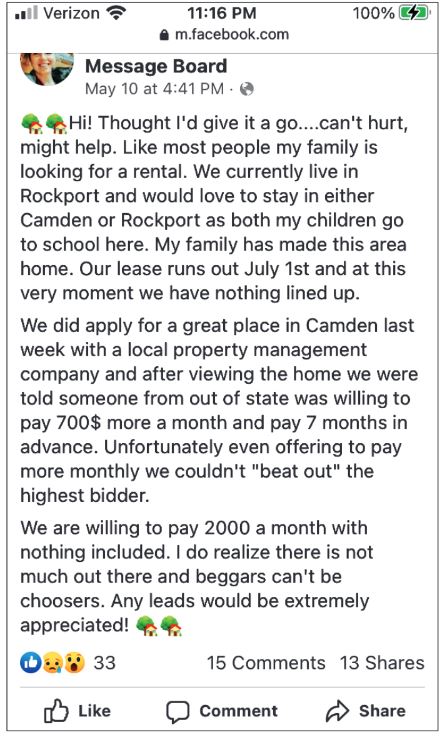

Posted on Midcoast Message Board this May: “Hi!..Like most people my family is looking for a rental…We did apply for a great place in Camden last week with a local property management company and after viewing the home we were told someone from out of state was willing to pay $700 more a month and pay 7 months in advance. Unfortunately, even offering to pay more monthly we couldn’t “beat out” the highest bidder. We are willing to pay 2000 a month with nothing included. I do realize there is not much out there and beggars can’t be choosers. Any leads would be extremely appreciated!” This went local-viral, gathering 33 crying, thumbs up, and wow emojis, 15 comments, and was shared all of 13 times, with one person commenting, “1800-2000 for a rent WTF has this world become!! And that is MAINE prices??”

Yes, $2,000 a month seems like a lot for midcoast Maine, especially because most of us here don’t make much money. But the truly startling part of the post was that the midcoast Maine rental market had apparently become so cut-throat that someone from out of state was flamboyantly, frantically throwing money at a landlord in hope of reserving a spot in The Most Picture Perfect Place in The World.

I reached out to the woman who had been outbid on the rental house. She told me that the house in Camden had entered the rental market at $1,800 a month. With an up-bid of $700 more per month, it became a $2,500-a-month rental (that’s $30,000 a year in rent). She said, “When I went and looked at the house I mentioned to [the landlord] that we lived in, worked in, and supported the community, and he essentially said he understood and that we had great references and had put our application in first, but that money is hard to pass up.”

Ultimately, she and her family ended up homeless. She, her husband and their two young children slept in friends’ basements for a month this summer. Only recently did they move into a long-term rental. She told me, “I would rather not be named, but it is so hard for people right now.”

I don’t tell this story to castigate whoever felt they needed to over-bid for the rental house in Camden. They were probably feeling the housing pressures as well. I tell it to illustrate the intense trends happening locally regarding housing, homelessness, and disparities in class and wealth, particularly during this grueling pandemic. As of June 30, in Knox County, the median real estate sales price has risen 33.36% in the last year, up to a whopping $337,500; in Waldo County, the median sales price has gone up by the highest percent in the entire state—almost 40%—to $260,000. According to the Knox County Homeless Coalition (KCHC), 63% of Knox county residents can’t afford the median priced home in the county. Houses here are going under contract after getting multiple offers in shocking speed, and are listed at ever-escalating prices, as many flee their homes elsewhere.

What about rentals? Local social media groups are now bursting with anxious renters describing heartbreaking situations, while others try to present themselves in attractive, detailed terms as if writing a match.com profile: “ISO a 1-2 bedroom house/apartment rental in the midcoast area (ideally) for a clean, quiet, professional couple and our well-behaved, non-destructive young female cat and ~50lb male dog.”

A recent Bangor Daily News article, “The Pandemic Made Maine’s Affordable Housing Problem Worse,” says Rockland has a median rent of $1,520, unaffordable to 73% of Rockland residents. According to KCHC, “Of the 95 intakes we did in 2020, the #1 reason for homelessness remains the inability to find affordable housing. This is followed closely by divorce, underscoring the economic challenges faced by single-earner households.” What counts as affordable? KCHC explained to me that rental affordability is calculated based on “the ratio of 2-Bedroom Rent Affordable at Median Renter Income to Median 2-Bedroom Rent.” Make your eyes glaze over? This was a little easier to understand: the median two-bedroom rent in Knox County is $1,062 per month “requiring income of $42,489 annually; however, the median household income of renters was only just over $35,000.” Try paying $30,000 a year in rent when you’re making $35,000.

Congress recently passed legislation to allocate billions to states to help renters, by way of the landlords, all of which helps to hold up the entire thin-string economy for everyone. Maine has $350 million in rent relief funds, and, like most other states, has so far distributed only a fraction of it—about $46 million. Maine Equal Justice writes that in July, 18,922 Maine households (including 6,967 with children at home) reported that they had no confidence they would be able to pay their rent for the next month. They encourage Maine renters to apply for the rental money, even if they applied previously and were denied, because more Mainers now qualify due to new rules for the program. The rent relief can cover 100% of rent and utilities for those eligible. Apply via Maine Housing: https://www.mainehousing.org/programs-services/rental/rentaldetail/covid-19-rental-relief-program. People can also reach out to Maine Equal Justice for help with applying, or concerns related to the process.

With more people leaving other states to find refuge in midcoast Maine during the pandemic, the pressures of gentrification are increasing. As the climate emergency escalates, and as long as Maine continues to be seen as a relatively climate change-buffered place to move to, these pressures will become ever more extreme. The problem isn’t about a particular person; out-of-staters, new Mainers, Indigenous Mainers, people of color, longtimers, people from every place on earth—we all belong here. The problem is that we as a society have decided it is acceptable for some to have multiple empty homes, and for some to have no home at all. The problem is that we as a society have decided that whoever has the most money gets the most choices. We must instead support healthy affordable housing projects in our communities; we need tenant protections like rent control, landlord registries, and longer eviction notification periods; we need to squat, ban, tax out of existence and/or reclaim empty homes; we need selective bans on non-owner-occupied Airbnbs.

These are all necessary, but until we insist that housing is a fundamental human right guaranteed everywhere on the planet, piecemeal attempts at housing policy will do little to hold back the perpetual inequality that capitalism demands. At the very least, those of us who are fortunate to have homes should consider opening them up to others to meet our local housing emergency head-on.