by Becca Shaw Glaser March 16, 2021, The Free Press

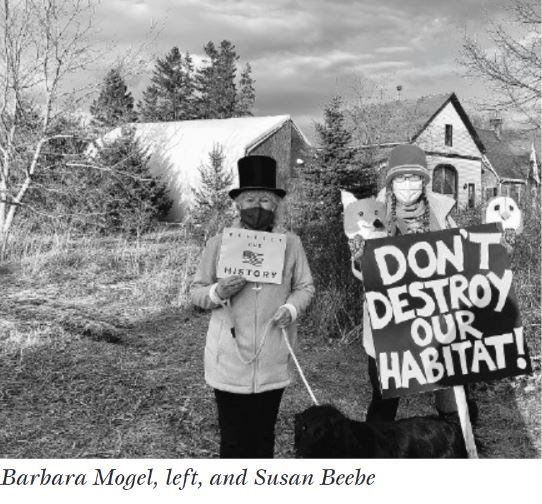

Rockland artist and activist Susan Beebe caught my eye by protesting at the site of a proposed housing development when the Rockland Planning Board toured the land on March 9. The proposal calls for eight efficiency rental houses, two rental duplexes and four single-family homes to be built by Habitat for Humanity and managed by the Knox County Homeless Coalition on a 10.6 acre bit of land on Talbot Avenue. The proposed homes are being discussed by the city because the plan requires a contract zone change. While Rockland code requires that homes be a minimum of 750 square feet, the eight efficiency homes in the proposal would be 500 square feet each. Planning Board Chair Erik Lausten told me that if someone wanted to build a 2,500-square-foot home on that property, or if the eight homes were made into four duplexes, no zoning change would be required. My interpretation is that Rockland’s code gives larger single-family homes primacy over more creative options that might better benefit people with fewer resources. A wealthier person could plop a 2,500 square foot mansion on the land, and those who are concerned about preserving the area for birds and fireflies wouldn’t have so many opportunities to chime in through official channels.

What intrigued me about Susan Beebe’s stance was that, while I usually find myself in agreement with her, I wasn’t so sure that I agreed that the Rockland Planning Board should reject this development. Although Susan had written eloquently about the fireflies, song sparrows and yellowthroats that live in this land that she calls “Firefly Field,” I wasn’t convinced that more housing for poor-ish people did not belong there. In a previous Notes from Lime City column, “Should Rockland Harbor Have Rights?,” Nate Davis and I discussed the idea of giving legal rights to those who do not have them in our political system: trees, water, air, birds, etc. I am moved by Susan’s question, “Why should a human habitat destroy habitat for everything else?,” and yet, I remain ambivalent, especially given that the proposal is to create (debatably) affordable housing and rentals for people in a city that is rapidly becoming more unaffordable.

Becca: One of the things I admire about you is your participation in the struggle against the Maine DOT, in a major attempt to try to save trees along Route 1 when they widened the road in Warren.

Susan: I didn’t know you knew about my efforts with Steve Burke and Jonathan Frost and many others to save trees [there] when the DOT widened the road in 2002. Yes, I climbed the Elephant Tree, a magnificent Horse Chestnut, and sat there for six hours until 2 policemen climbed up and “made” me get down. I had heard they had threatened people sitting in other trees with tear gas, and I was afraid of that, or that they would pull me and make me fall. I was sitting in a deer stand that Steve had placed high in the tree. Two young women, one pregnant, were sitting in a small platform lower down, and two young men had chained themselves to the trunk. I had spent the night before lying on the 2nd floor of the barn by the house, with the owner’s permission, so I could climb the tree at 6AM. I didn’t sleep; I stared into the darkness most of the night. Fifteen people were arrested in what I believe was the biggest civil disobedience the midcoast ever had.

Becca: I have a vivid image in my mind of the painting you made of the “Elephant Tree.” It has stuck with me for years.

Susan: Jonathan and I had organized about 25 local artists to paint trees or scenes that would be destroyed by the road construction. I spent three days painting the Elephant Tree, so-called because a circus elephant had tried to eat it and pulled it sideways when it was a sapling. This is what the people across the street told me. While I painted, I fell in love with the gorgeous tree, then in full bloom, in early June, with hummingbirds visiting the white “candles” of blossom, and that’s when I decided to sit in it.

Later we had a show of all the artwork that we called “Remove Tree,” because that was written on the stake by the Elephant Tree, at the Lincoln Street Center. I was allowed to bring my painting into the Knox County Courthouse as “evidence.” I was convicted of criminal trespass and chose to pay a fine of $180. There was so much outrage, even internationally, about the cutting of more than 80 trees and the desecration of the neighborhood, that the head of the DOT resigned!

Two years later, when the DOT came to Camden with a plan to cut down more than 150 trees along Route 1, we were ready for them, and they really had to scale back their plan. Again we had artists participate, because that allows emotions to be released and people feel they can speak up for beauty, an intangible and incalculable value.

Becca: While I usually share your ethics and beliefs, I wasn’t immediately in agreement with your plea that the Habitat for Humanity homes and rentals not go in at the proposed Talbot Avenue location in Rockland. It’s not that I don’t adore fireflies and swampy areas, and want many of those areas to be left as they are, but there are desperate needs for human housing locally as well.

Susan: I see a connection between the widening of Route 1 and the proposed development on Firefly Field. Both were plans drawn by engineers on paper without those engineers knowing what was really there. I am speaking from my knowledge of 10 years of walking by that field and observing what is actually living there, from plant life to insect life to bird life to the evidence of mammals passing through, and some of them hunting in the field, revealed by their tracks in the winter. In this case, the plan as drawn out IS in direct conflict with the creatures that already live there. It will almost surely result in the disappearance of the fireflies.

Becca: Much of the history of the environmental movement has seen environmentalists juxtaposing the needs of humans as if in direct contrast with the needs of all other living beings. At times this has led to the environmental movement being eugenicist, fiercely anti-immigrant (the bankrolling of the Right-wing by Cordelia Scaife May, for instance), and perpetuating a false idea that human overpopulation is the primary problem. It seems far more accurate to say that a very small share of the human population has an extremely outsized share in human destructiveness. How do you suggest we balance the needs of everyone?

Susan: I agree with you about the failings, racism and shortsightedness of the environmental movement. I agree that we need housing for poor people. I think we need to have a community forum on how this can be done, balancing the needs of humans and nature. Of course we are connected, part of nature.

Becca: I don’t think that critics and activists should always have to come up with the solutions, but I am genuinely interested in where you would suggest Habitat for Humanity build, if at all (I know that not everyone is a fan of Habitat for Humanity)?

Susan: If that land must be built on, it would be better to build an apartment building at the back, north side of the lot, where the ground is slightly higher and drier. That could be designed to require a lot less heating than 15 individual small houses would. Also the parking would be concentrated in one area. And it could be designed with a minimum of lights at night, to minimize light pollution. The damp field in the front, toward Talbot, and the stream with the swamp, should be left alone.

I would be happy to live in an apartment at the Lincoln Street Center, or the McLain School, or a downtown building, as long as I could get outside and work in a garden at a public park, and walk to natural areas. That’s another point: Firefly Field is within walking distance of downtown; it’s important for people to see the richness of a real natural area, and a dark place at night. I hear, “Oh, Maine is such a beautiful place, there are so many places to explore!” Well, what if you don’t have a car or don’t drive?

Another thing is that grasslands and wetlands absorb a lot of carbon as well as filtering water. We need to restore habitat in places where native plants have been removed or taken over by invasive plants. We need to break up some of the sea of asphalt that covers the downtown and funnels runoff into the harbor. For places to build, it would be better to cut down a stand of Norway maples and bittersweet, invasive plants that contribute nothing to the ecosystem (they photosynthesize, but since almost no native insects eat them, that energy from the sun doesn’t go into the food web), than build on a productive, healthy wetland, whose health is indicated by the presence of fireflies.

Becca: What was it like protesting with your sign when the Planning Board came?

Susan: We got a lot of “thumbs up” from people driving by and no “fingers!” I spoke up at the end of the Planning Board meeting, listing all the animals I know, from tracks in the snow or neighbors’ wildlife camera reports, that use or pass through the field and wetland: bobcat, fisher, coyote, fox, wild turkey, mink, weasel, raccoon, deer, voles. At least the head of the Planning Board mentioned fireflies and song sparrows after we read our letters, so they became part of the conversation. But they don’t really get it: that one piece of land is not interchangeable with another; THIS place is special because of the rich biodiversity that exists there.

Becca: How do you keep the strength, passion and balance to put yourself out there?

Susan: Because I have to use the time that is given me to try to make a difference, to stand up for the creatures that have no voice.